Euro emission standards didn’t just set pollution limits and walk away. They fundamentally changed how motorcycles are designed, what manufacturers can build, and what riders can buy.

Some changes are improvements. Some are frustrating. Most are just the reality of complying with increasingly strict regulations.

Let’s talk about what actually changed—and why.

The Most Obvious Change: Exhausts Got Huge

Look at any motorcycle from the 1980s or 1990s. Now look at a 2024 model. The exhaust system is probably twice the size.

Why? Catalytic converters.

Catalytic converters are mesh or honeycomb structures coated with metals (platinum, palladium, rhodium) that trigger chemical reactions in hot exhaust gases. These reactions convert harmful pollutants—carbon monoxide, hydrocarbons, nitrogen oxides—into less toxic substances like carbon dioxide and water vapor.

They work. But they’re bulky, expensive, and require careful integration into exhaust design.

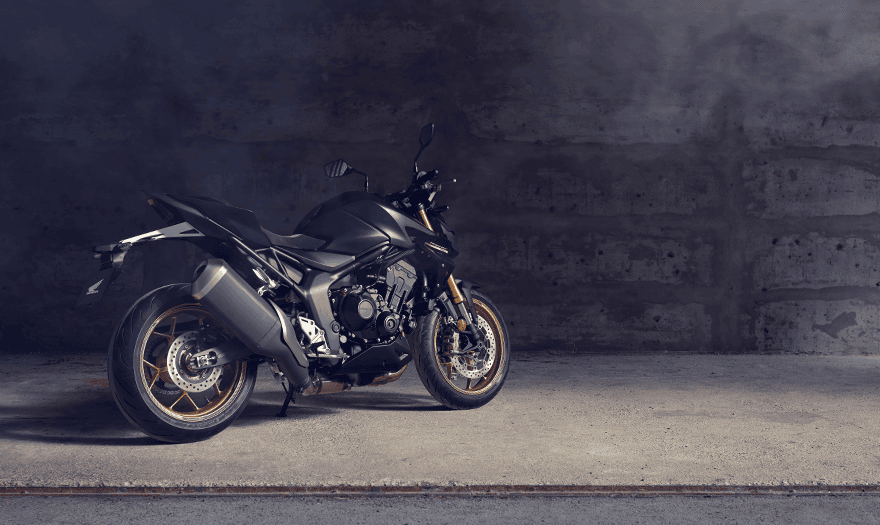

Example: Compare a 1983 Honda CB1000 Custom (simple, narrow pipes) to a 2025 Honda CB1000 Hornet (massive underseat exhaust). The difference is entirely about emission compliance.

Honda CB 1000 Custom Motorcycles – Photos, Video, Specs, Reviews | Bike.Net

Some riders hate the look. Others don’t care. But everyone’s paying for it—catalytic converters aren’t cheap, and redesigning exhausts around them adds cost.

Do you prefer the cleaner look of older exhausts, or are modern systems fine?

The Disappearance of 1000cc Sport Bikes

High-revving, high-displacement sport bikes are dying out in Europe. Not because riders don’t want them—because manufacturers can’t make them Euro-compliant without massive expense.

The technical problem: High-revving engines (think 10,000+ RPM redlines) have longer valve durations. This increases hydrocarbon emissions during combustion. Meeting Euro 5’s strict hydrocarbon limits (0.1 g/km) is extremely difficult with traditional literbike engine designs.

The solution: Smaller displacement, lower redlines, different engine characteristics. Many manufacturers shifted from 1000cc to 900cc platforms. The power difference isn’t huge, but the emissions compliance is easier.

Examples of discontinued or redesigned bikes:

- Yamaha Niken GT (discontinued 2024)

- Various 1000cc supersports either gone or replaced with 900cc versions

- Some traditional naked bikes redesigned entirely

For riders who love high-revving engines, this is a loss. For the environment, it’s progress.

Would you rather have a 900cc Euro 5-compliant bike or a 1000cc that doesn’t meet standards?

Ride-by-Wire Throttles: Necessary Evil or Genuine Improvement?

Older motorcycles had cable throttles. You twist the grip, the cable physically pulls the throttle valve open. Simple, direct, mechanical.

Modern bikes have ride-by-wire throttles. Sensors in the grip send electronic signals to the Engine Control Unit (ECU). The ECU considers your input plus other factors (speed, gear, traction, lean angle, riding mode) and adjusts the throttle valve electronically.

Why this happened: Euro standards require precise control of fuel delivery and emissions. Cable throttles can’t integrate with advanced engine management systems. Ride-by-wire can.

Benefits:

- Smoother, more predictable throttle response

- Better integration with traction control and riding modes

- Enables fuel cut-off during deceleration (reduces emissions and improves efficiency)

- Safer in certain situations (ECU can limit power if sensors detect problems)

Downsides:

- Some riders hate the “disconnected” feel

- More complex, more expensive

- One more electronic system that can fail

Personally? I think ride-by-wire is fine when done well. Yamaha’s been using it for years (they call it YCC-T), and most riders don’t even notice it’s electronic. The 2023 Niken GT has ride-by-wire, and reviews praise the throttle feel.

But I understand why some riders prefer the direct mechanical connection of cables.

Variable Valve Timing (VVT): Expensive But Effective

Another technology driven by Euro standards: Variable Valve Timing.

Traditional engines have fixed valve timing—valves open and close at the same points regardless of engine speed. This is a compromise. What works well at low RPM doesn’t work as well at high RPM, and vice versa.

VVT adjusts valve timing dynamically based on engine speed and load. This optimizes combustion across the rev range, improving:

- Power delivery

- Fuel efficiency

- Emissions control

The problem: VVT systems are complex and expensive. They add cost to manufacturing, and potentially to maintenance.

The benefit: Engines perform better while emitting less. You get stronger low-end torque, smoother mid-range, and better top-end—all while meeting strict emission limits.

Is it worth the cost? Manufacturers think so. Most modern high-performance bikes use some form of VVT.

Have you ridden a bike with VVT? Did you notice a difference?

On-Board Diagnostics: Helpful or a Future Headache?

Euro 4 introduced OBD Stage I (On-Board Diagnostics). Euro 5+ requires OBD Stage II, which is more comprehensive.

What OBD does: Monitors emission-related components (catalytic converters, oxygen sensors, fuel systems) and alerts the rider if something fails or degrades.

In theory: This is good. You know when emission systems need service. Problems get caught early.

In practice: Some riders worry this means bikes will throw error codes more frequently, potentially limiting performance or requiring expensive repairs. If an oxygen sensor fails and triggers a warning light, can you still ride? Will the bike go into “limp mode”? Will repairs cost more because everything’s monitored electronically?

Time will tell. But it’s a legitimate concern, especially for people who want to keep bikes running for 10-20+ years.

Durability Requirements: Emission Systems Must Last Longer

Euro 5+ requires manufacturers to prove emission control systems remain effective for at least 20,000 km, often longer depending on the bike.

This is good: Components should last longer. Manufacturers can’t use cheap parts that degrade quickly.

This might be bad: When emission components do fail after 20,000+ km, replacements might be expensive. Catalytic converters, oxygen sensors, advanced fuel injection systems—none of this is cheap.

Long-term ownership costs could increase. Or, if systems genuinely last longer, maintenance intervals might stretch out and total costs could stay similar.

We won’t know for years how this plays out.

Real Driving Emissions (RDE) Testing: No More Lab Tricks

Euro 5+ introduced Real Driving Emissions testing. Instead of just lab tests under controlled conditions, bikes are tested on actual roads in real-world conditions.

Why this matters: Some manufacturers were optimizing bikes to pass lab tests but emit more in real-world riding. RDE testing closes that loophole.

Result: Bikes that actually meet emission standards in normal use, not just in perfect test conditions.

This is unambiguously good. If we’re going to have emission standards, they should reflect reality.

The Cost Question: Are Bikes Too Expensive Now?

All this technology—catalytic converters, ride-by-wire, VVT, OBD-II, redesigned exhausts, advanced fuel injection—costs money.

Upfront: Bikes are more expensive than they used to be. A significant portion of price increases over the past decade is emission compliance.

Long-term: Uncertain. Better fuel efficiency might save money. But complex electronic systems and emission components might cost more to maintain or replace.

For some riders, higher upfront costs are worth it for cleaner air and potentially better performance. For others, it’s pricing them out of motorcycling entirely.

Has the cost of new bikes affected your purchasing decisions?

My Honest Take

Euro standards forced manufacturers to innovate. Engines are cleaner, more efficient, often more powerful than older designs. Technology like ride-by-wire and VVT genuinely improves the riding experience when done well.

But there are losses: simpler designs, high-revving engines, mechanical purity, lower costs. Some beloved bikes disappeared because they couldn’t be made compliant economically.

Are motorcycles better overall? Depends on what you value. Cleaner emissions? Yes. More technology? Yes. More expensive? Also yes.

I think most changes are net positive, but I understand why riders miss the simplicity and rawness of older bikes.

The landscape changed. We’re not getting the old days back. The question now is whether future regulations (Euro 6, the 2035 ICE ban) push things too far or continue improving what we ride.

What’s your take? Are these changes making motorcycles better or worse?